The Sport That Went from 'Behind the Home Depot' to ESPN and NBC in Five Years

How Drone Racing League channeled grassroots DIY internet fandom into expertly produced, sci-fi inspired entertainment with patented drone technology.

"It was very amateur, underground, but there were moments that made me feel like I was inside Star Wars," remembers Nicholas Horbaczewski. It was 2015, and he had been invited to watch his first drone race, held in an abandoned lot behind a Home Depot in Long Island.

As homemade drones raced by, competing to complete a set track as quickly as possible without getting sideswiped or wiping out, he wondered what it would take to make this hobby phenomenon into a full-force cultural movement.

"I felt like I was getting to touch and experience something that had been promised to be part of the future. It reminded me of the sports that had only existed in science fiction movies and video games," he says. And as he researched more, it became clear he wasn't the only one who felt that way. "Everywhere I looked, there was organized amateur underground drone racing, meeting up at secret fields and parking lots. There was no money behind it, no media. It was just unbelievable; there's this complete culture going on and the rest of us didn't know about. How do we bring it to the rest of the world?"

Horbaczewski thought he might be the one to do it. He had previously founded a video production company, sold drones and other consumer tech to the government, and served as Tough Mudder's Chief Revenue Officer. Months later, he was inviting top-tier pilots, potential media partners, and investors to Drone Racing League (DRL)'s first competition.

Now, after airing three seasons on ESPN and international networks, DRL is preparing for the premiere of their fourth season this Sunday, August 11 at 2pm ET. It marks their first appearance on NBC and Twitter, and their first time offering a consumer-friendly version of the drones their professionals fly, live on Kickstarter now.

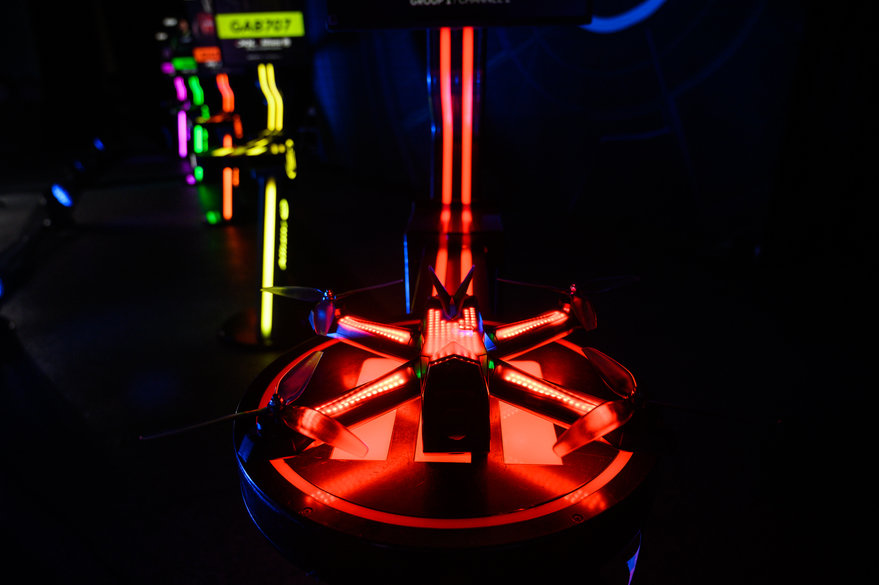

The DRL Racer4 Street is a consumer drone modeled after the ones professional pilots use.

The DRL Racer4 Street is a consumer drone modeled after the ones professional pilots use.

In just five years, Horbaczewski has grown an underground hobby sport into an internationally-broadcast "real-life video game" that's reached millions of viewers—but it wasn't all smooth sailing.

Unexpected horror at Gates of Hell

DRL's first race, in 2015, was staged at the Gates of Hell, a dystopic-looking locale of suburban-legend fame in New Jersey. Horbaczewski's team had been frantically coordinating drone development, video production, and promotion plans—"we were trying to bring all the pieces together at the same time, using off-the-shelf components to get the tech ready to go"—only to find that developing the tech should have been their first priority.

"When we got to the Gates of Hell, everything went wrong," Horbaczewski says. "It lived up to its namesake." The stress test of a real race put their tech to shame—the drones had to fly further than a recreational one normally would, and there were too many in the air at once. Components didn't work consistently, radio signals failed, and the LED lights that differentiate drivers weren't bright enough. Crashes abounded.

"There was sort of a growing realization of what we were getting ourselves into," Horbaczewski says.

They made the most of it. The DRL team reset expectations for the VIP crowd they invited, reframing the event as a demo instead of a race. And they recorded footage that would define their aesthetics.

The Gates of Hell race fell through, but it set the tone for DRL's visual style.

The Gates of Hell race fell through, but it set the tone for DRL's visual style.

Their videographers from Culprit Creative patchworked together inspiring scenes to illustrate how exciting drone racing could be (once the drones really worked). "It was cool, slick, music video-type stuff that shaped our ethos on filming drones. It showed the speed—honestly, the sexiness—of the technology. They came up with the concept design of these bright neon lights we still use to this day. That futuristic element worked."

"There were moments of greatness," Horbaczewski says, "but the truth is that we were still trying to use off-the-shelf technology in an industrialized setting. It's not the right tool for the job."

Entertainment-grade drones demand more than off-the-shelf or homemade models

"Sexy" sci-fi shots couldn't carry DRL. "After Gates of Hell, we stepped back and said, 'All the sci-fi movie talk is irrelevant if the tech doesn't work,'" Horbaczewski says. "So we became a technology company. We focus on making the tech awesome and let that facilitate a really cool futuristic experience."

DIY races typically are BYOD (bring your own drone), but DRL thought it was important to standardize the tech. "We wanted everyone to be racing the same drone," Horbaczewski says. "We were looking to find the greatest drone racing pilot on earth, not the person who could build the fastest drone.

"We also thought that the drone you build to go race with your friends through a parking lot somewhere is not the same thing that you want to watch as a spectator. We were trying to give the sport the elements that would make people willing to watch it either in person or on television—that means the drones have to be really brightly-lit and color-differentiated, carry a camera that could film HD footage, and connect to a radio system that won't fail when there are lots of other drones and spectators on their cell phones nearby. You're not going to worry about those things on your homemade drone. But we worry about those things."

So the DRL team created a proprietary, patented suite of technology—drones that are as good at barrel rolls as they are at capturing HD footage, software flight simulators to train pilots, a custom radio system, a timing and scoring system, and a fleet-management system that can track and remotely control 600 devices at once. "We actually made the tech that made it possible to realize this, in hindsight, very ambitious vision."

They improve this system—particularly the drones—every season. Races become a product reveal moment, like Spring Training meets WWDC. They generate a similar frenzy of early-adopter excitement, too. The fans want drones.

"Through email, on social, it's like, 'Take my money,' 'Why won't you sell this to me?' 'How do I get my hands on this drone?'" Horbaczewski says. "I think it's awesome for us. It shows how passionate people are about it. It's a respectful compliment to the design that goes into it. It touches on the aspirational element of DRL, that it's this cool, new pro sport."

So, for the first time, DRL is releasing a consumer version of their drone. The DRL Racer4 Street has all the fine-tuned engineering as the models that pros fly, without some of the industrial-grade add-ons that amateurs wouldn't really need.

The DRL Racer4 Street is based on the Drone Racing League's fourth-generation racing drone.

The DRL Racer4 Street is based on the Drone Racing League's fourth-generation racing drone.

A sport taken straight out of sci-fi movies and video games

The drones might not be as exciting—and might not have picked up airtime on ESPN, NBC, Twitter, and networks in the U.K., Germany, and China—without the professional, futuristic production values DRL established early on.

The video game inspiration has stayed central to DRL's aesthetic identity. They call their events "levels" and create themed sets like "LA Apocalypse" and "Project Manhattan." Ashley Ellison, who runs operations, has a knack for finding abandoned malls and factories to create this sense of environment. Tony Buddy, director of media, figures out shots that make the action easier to follow.

"My favorite racing video game growing up was F-Zero," Horbaczewski says. "The cars crash all the time and explode, and there's this futuristic quality to it. The tracks are on these incredible environments." He also draws inspiration from Mario Kart, "maybe the most universal racing game ever played,"—also full of elaborate environments and interaction between the players.

Many pilots literally start this sport in a video game. The first time you pick up a controller, you'll probably crash the drone you're trying to fly. So DRL made a custom training simulator for Steam. It's how Horbaczewski learned to fly drones. "It's another thing that makes the sport feel futuristic, but also demystifies it and I hope makes the sport more accessible," he says. "Like me, you can learn entirely in a video game and walk out and do it in real life." A quarter million users have now tried it, and some of the league's top pilots, with backgrounds ranging from downhill skiing to gaming, trained almost entirely online before winning DRL races.

"We are innovating our technology to keep striving towards making DRL as much as a real-life video game as possible," Horbaczewski says. "Sometimes people tell me, 'Oh no, it'll change every year.' I'm like, 'Yeah, it will change every year forever. It's not a static sport. We're going to evolve as the technology evolves. We're trying to create the complete, real life version of Mario Kart. We're trying to bring those things that have only existed as computer-generated graphics to real life. And I think that's really fun."

DRL Racer4 Street is live on Kickstarter through October 5.

—Katheryn Thayer

-

oFavorite This

-

QComment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.