Where Does Generative Design Belong? Designers Must Decide

I'd prefer it was invisible

Ten years ago generative design was not a widely available technology (unless you were running Rhino and Grasshopper). Today it's integrated with Fusion 360. As the technology becomes ubiquitous, designers who have avoided thinking about it will be caught flatfooted. Even if you yourself are not currently in a position to use it, it's likely you'll encounter it in future projects. The smart money says you should consider GD's place in modern design and form an opinion on how the technology ought be wielded.

The non-I.D. layperson may not have ever heard of Rhino, Grasshopper, Autodesk. But everyone's heard of Volkswagen, and the German automaker recently released shots of a classic Microbus design touched up with Fusion-based generative design elements, created in collaboration with Autodesk. That's meant to build consumer awareness of GD. But before I get into that, let's look at what the technology promises, within the context of what came before.

Figuring out how to create strong structures has been the domain of mankind, ever since the first pioneering caveman decided he was done with caves.

"Let's move to the coast."

"Let's move to the coast."

Fast-forward dozens of millennia, and man had figured out timber frames. By observing basic geometry and learning to interlock different members together in a particular way, mankind learned to build incredibly sturdy edifices, which have since been proven to withstand earthquakes and even atomic blasts.

Once we got into metal and mass manufacturing, engineers perfected the steel truss. The support elements were a lot finer, and the assembly of them more straightforward; it was easier to teach a guy named Jack to weld than to teach someone named Josiah to saw and pare a half-lapped dovetail joint.

Steel trusses, of course, changed structural design forever. With the ability to create large spans, architects could now create megachurches, convention centers and casinos with a minimum of support columns.

Industrial designers employ support trusses on a smaller scale. These can often be invisible, inside an injection-molded part…

…or left visible as a functional but stylish element, like on a Ducati Monster 797.

Car rims are another area where structural function and design style can be combined.

Which brings us to the latest example of generative design: The vintage Microbus cooked up by VW and Autodesk. VW's Innovation and Engineering Center California retrofitted an existing 'Bus with an electric drive system, and to strip weight from the vehicle, turned to generative design for some of the components. Exhibit A: The GD'd rims, which provide the required structure while cutting the weight by 18%:

"With generative design it's possible to create structures that we, as human designers and engineers, could never have created otherwise," said Andrew Morandi, senior product designer, Volkswagen Group. "One of the biggest surprises for me was seeing just how much material you could remove from a conventional wheel structure."

They also applied generative design to the sideview mirror mounts, the steering wheel and the rear bench supports:

"A steering wheel is not a particularly heavy component but it's the primary touchpoint for the driver. People aren't really accustomed to touching mounts or supports," said Erik Glaser, principal product designer, Volkswagen Group. "We wanted to put a generatively designed object in a place where people will touch it because not only is it intricate and beautiful, but it can also give a sense of just how strong these parts can be."

This is subjective, but I really do not like the look of these GD'd elements. If you look at the conventional trusses pictured earlier in this entry, you see the hands of man, historical progression. The timber frames, the structures and the Ducatis were designed by the same species.

When I look at the generatively-designed trusses, I see an unnatural combination of organic and technological that read to me as grotesque. I know this is an irrational view; if we look inside the tissue, bones and organs of our own bodies, we'd see similarly optimized and yet random-appearing structures.

Which is where I stand on it--I'd like the benefits of generative design to be largely invisible, used for internal support structures rather than highlighted as aesthetic elements. I'd like for the machine to deliver us the cost and material savings behind the scenes, while human designers are responsible for the forward-facing elements.

Indeed, when I first got to see generative design up close at Autodesk University some years ago, it wasn't the shot of a GD'd chair that impressed me…

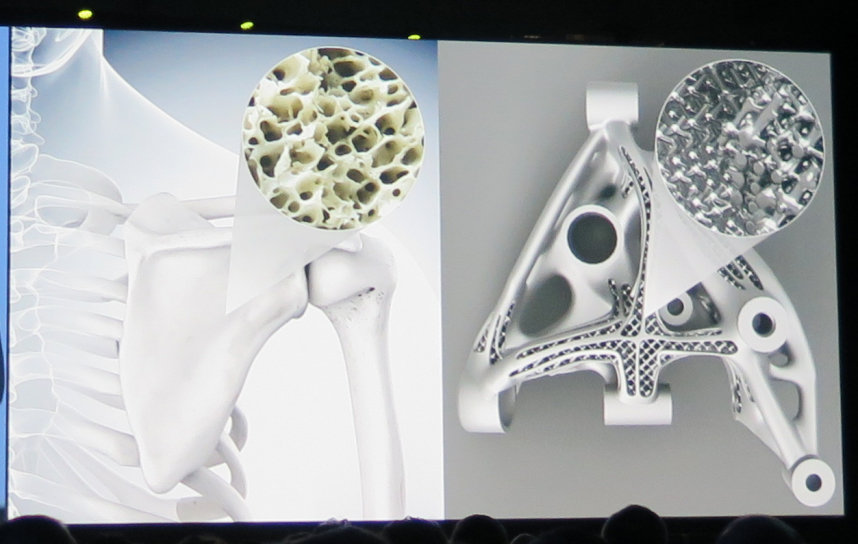

…it was a human-bones-based automotive suspension component that drove the potential home to me. It featured a GD'd weight-saving internal lattice that no human could have devised:

As I wrote back then, "The software isn't filling the void with the same repeating pattern. It actually mimics bone by adding material only where it's necessary and removing material where it's not." That's something a human designer cannot do--not in a time-efficient way, in any case--and where the machine can spit out thousands of variants relatively quickly. That is where the machine's strengths lie, not in aesthetic presentation, so I hope that that latter part will be left to human designers.

Ultimately, however, my viewpoint doesn't matter; it will be up to the current and next generation of designers who have the agency to decide how they will incorporate GD into their designs. It will then be up to our corporate masters to greenlight those designs, and finally for the end users to vote with their dollars.

Given the choice, do you think designers should nakedly expose GD'd elements? Is this something that ought be accepted as an aesthetic in its own right?

_________

Up Next: What do practicing industrial designers think of generative design? As it turns out, Core77 forum members have been having this discussion--starting nearly ten years ago. If you were to print out the entire discussion to date, it'd be more than 100 pages. We'll cull through the entire thing and present you with the salient points.

-

o2Favorite This

-

Q14Comment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.

Comments

This was awesome!

Every technology that allows designers to make things differently is over-used and then perceived as "cheap", it has happened many times before and it will happen again. About GD, I think the structural capabilities will be more interesting and useful than the mere "organic tissue" look.

coool

I think GD can be aesthetic in the right applications, or with some tweaks. I agree with you, however, on the point of "I'd like the benefits of generative design to be largely invisible, used for internal support structures rather than highlighted as aesthetic elements". I think of it like I think of any other DFM- or 'engineering'-driven element. Ribs in a molded element are typically ugly, or at least, resolving them aesthetically presents a significant challenge. Hiding them behind a disparate aesthetic surface may be lazy, but it looks good. Leaving them exposed and making zero attempt to improve them aesthetically is even more lazy, and looks awful. However, if the subject of the design effort relies on highly-optimized engineering in order to be successful (i.e. aerospace industry), having visible structural elements may be a consequence of the optimization. In this case, spending the time to resolve the structure aesthetically can result in some surprisingly attractive aesthetic results.

To be clear, that effort was not made on the VW example above. Applying a smoothing function and painting it orange does not an attractive GD element make. Examples of well-resolved GD that come to mind are the Adidas Futurecraft 4D (allowing a GD element to drive a cohesive aesthetic, good hierarchy), Starck A.I. chair for Kartell (well-resolved GD elements without going overboard), and the ceiling of the University of Iowa's Voxman School of Music concert hall (blending multiple functionalities and design requirements while also accomplishing an impressive aesthetic -in a ceiling- is impressive to me, at least).

In summary, I agree with you for the most part, but I'd like to see designers continue to make the significant effort required to push the aesthetic envelope of GD and drive new and interesting designs without feeling like these things always need to be completely hidden.

Not mentioning Jake Evill's 'Cortex' 3D printed arm cast was a mistake. That's a perfect example of well-executed GD driving a _better_ aesthetic than I've ever seen in a perfectly appropriate application.

Problem is manufacturing

Actually the wheels are cast.

There are many generative design tools take into account manufacturing processes- these ones are of course geared towards additive or costly 5+axis machining but I've seen 2/2.5/3 axis generative design tools as well as the use of generative design to drive welded assemblies. I've admittedly seen less with molding but its still feasible that as the technology matures it will be more refined to practical application.

I think Generative and Parametric design are brilliant, but it's up to designers to use them correctly. With the right inputs and boundaries I think it could make a very interesting and aesthetically pleasing element of a larger designed object. I remember seeing some prosthesis and medical forms designed parametrically, and I thought they fit their use and had a fashionable element to them... which I don't think VW captured with this project.

The main problem I see with the VW concpet is that these structures are not credible. I don't believe they gain weight, I don't believe the structure is more sound. The seat foot is ridiculous in itself (and will be a mess to clean). It is style over design.

I agree with the rets of your take, GD can be very interesting for intrenal structure, and maybe for other uses, the exemples so far are quite bad.

I've wanted to play with this for years but I'm a solidworks/alias guy.

I saw an article on it that used GD to come up with the general concept, then the designer 'surfaced' the web like structure to create something beautiful, striking, and manufacturable.

I agree with the invisible standpoint as well, I appreciate the technology is early in its development but its clear strong suit is mostly mechanical, not aesthetic. In fact, I think most of the products that are trying to use generative design as an A-surface exercise are as you explained as "grotesque." Good designers will definitely adapt, however, there is something disappointing about a technology possibly disrupting a lot of the things many (most?) designers enjoy about designing in the first place and leaving the profession to decide if its what they want to continue to spend their life doing. Nice write up, I am looking forward to continuing to explore GD and see where it takes us, hopefully on a positive path!

Resonates a little with another article I read (I thought on Core but now can't find it) about the proliferation of parametric/computational design in architecture and how now that an everyone and their mother can throw a Voronoi cell structure at a render and call it a day the distinction between talent and mere visual interest was muddied (should that matter idk).

Yeah was thinking the same - if its looking grotesque or misplaced could it be that the inputs are insufficient?