Nanda Vigo, Space-Time Explorer

This is the third installment of our new Designing Women series. Previously, we profiled Marianne Brandt and Belle Kogan.

Nanda Vigo's website is a great place to start a cosmic journey—UFOs streak across the page, stars ricochet, intergalactic transmissions ping to life, and your navigation button is an icon of the USS Enterprise. Much like Vigo's physical creations, it's an idiosyncratic exploration of the future with a dash of pop culture.

Nanda Vigo surrounded by her designs. Photo by Gabriele Basilico

Nanda Vigo surrounded by her designs. Photo by Gabriele Basilico Vigo, who is now 79 years old and still working, has been pursuing designs based on something she calls "chronotopical" theory—from the Greek for "time-space"—since starting her Milan-based studio in 1959. I can't pretend to entirely understand her theory (it has to do with "the continuous and complete understanding of man beyond the form," if that helps); suffice to say that Vigo wants to activate and enhance the viewer's sensory perception of space and time—often through the use of industrial materials like glass, mirror and neon.

Over her six-decade career, Vigo's work has spanned light fixtures, interiors, architecture, furniture and conceptual light-art installations. Her earliest works from the 1960s, called Cronotops, are structures of glass, aluminum, mirror and neon that reflect and diffract light. With these works, she found a kinship with the German group Zero and its worldwide network of artists, who sought to redefine the post–World War II visual landscape. (For more on Zero, see the Guggenheim's recent exhibition ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s, which included Vigo's Cronotops.)

Aluminum and glass Cronotop, 1963

Aluminum and glass Cronotop, 1963 Beginning in the late '60s, Vigo began to take on commercial lighting commissions, including several light fixtures for Kartell; acclaimed designs for Arredoluce like the Golden Gate, Iceberg and Utopia fixtures; and, in the '80s, her Light Trees for Lumi.

A pair of Golden Gate light fixtures for Arredoluce, installed in Vigo's interior for La Casa Che Non C'e, 1972

A pair of Golden Gate light fixtures for Arredoluce, installed in Vigo's interior for La Casa Che Non C'e, 1972 Tables, chairs, mirrors, rugs and household objects would follow, all of them imbued with Vigo's space-age eclecticism. Standouts included a sleek suite of glass-and-mirror furniture for FAI International and the tubular-steel-and-faux-fur Due Più chairs for Conconi.

A table and chair from the Top collection, manufactured by FAI International, 1970

A table and chair from the Top collection, manufactured by FAI International, 1970  Vigo's Mobile Sound credenza for FAI International, 1970

Vigo's Mobile Sound credenza for FAI International, 1970  The Mobile Sound credenza with all of its compartments open

The Mobile Sound credenza with all of its compartments open  A pair of Due Più (translation: "Two More") chairs manufactured by Conconi, 1971

A pair of Due Più (translation: "Two More") chairs manufactured by Conconi, 1971 Vigo also applied her radical vision to architecture and interior commissions, most famously in a museum-home in Lido di Spina, Italy, for the artist and collector Remo Brindisi. Domus called the structure a "dwelling museum," as it allowed Brindisi to live amongst his collection of 1,800 works of contemporary art—displayed in Vigo's appropriately avant-garde setting of white-tiled walls, mirrors, neon lights and mirrored furniture.

The central rotunda exhibition/living space of Casa Museo Remo Brindisi, designed by Nanda Vigo, 1971–73

The central rotunda exhibition/living space of Casa Museo Remo Brindisi, designed by Nanda Vigo, 1971–73  Ground floor plan of Casa Museo Remo Brindisi, published in Domus, February 1974

Ground floor plan of Casa Museo Remo Brindisi, published in Domus, February 1974 Arguably, her grooviest commission was an interior for a 1964 Gio Ponti house named Lo Scarabeo Sotto La Foglia (The Beetle Under the Leaves). Here, her signature white-tiled walls and floors created a monochromatic backdrop for interior elements clad in so much shaggy fur that they could be mistaken for props from the set of Barbarella. Other interiors completed by Vigo expanded on this monochromatic theme, limiting each space to a single color.

Circular fur-clad staircase inside Lo Scarabeo Sotto La Foglia, Malo, Italy, 1965–68

Circular fur-clad staircase inside Lo Scarabeo Sotto La Foglia, Malo, Italy, 1965–68 A view of the staircase from above, and an equally furry seating arrangement

A view of the staircase from above, and an equally furry seating arrangement Monochromatic design for La Casa Blu, Milan, 1967–71

Monochromatic design for La Casa Blu, Milan, 1967–71 Still creating and exhibiting today, Vigo showed her latest series of light art, Deep Space, earlier this year in Genoa, alongside some of her older pieces. Her multidisciplinary work continues to unveil new universes of experience, or as one critic recently put it, "vibrations of the invisible world."

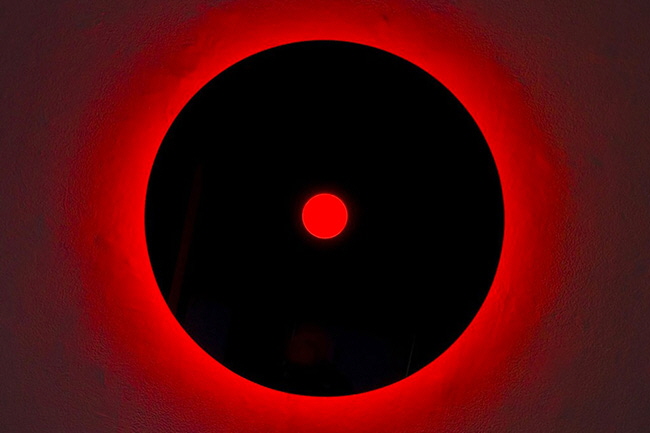

Genesis Light from Vigo's recent Deep Space series

Genesis Light from Vigo's recent Deep Space series  Light Tree for Lumi, circa 1980

Light Tree for Lumi, circa 1980  Mirror with neon inserts for Glas Italia

Mirror with neon inserts for Glas Italia Lamp design for Kartell, featured in Design magazine

Lamp design for Kartell, featured in Design magazine Chrome directional lamp for Arredoluce, featured in Design magazine

Chrome directional lamp for Arredoluce, featured in Design magazine -

o1Favorite This

-

QComment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.