A Brief History of Golf Ball Design, and Why You Shouldn't Hit People with Baseball Bats

I once helped a career criminal move some things out of his basement—long story—and when we got to his golf clubs, he hit me (not literally) with this factoid: A golf club is apparently the ideal implement for casual, everyday interpersonal assault.

"I thought [guys in your line of work] used baseball bats," I said, naively.

"Nah," he said. "Those are too big and heavy. You come at me with a bat and I can take it away from you. But this"—he turned around and swung a golf club back and forth through the air, causing it to make a creepy whistling noise—"you don't see this coming, it's so fast. And you can't get it away from me. Look at the rubber grip on this thing." Ergonomically superior, he said, though in more colorful terms. Lastly he pointed out that if you get pulled over and the cops find a bat in your trunk, you get a second look; but a set of golf clubs never prompts questions.

Other than that story I have nothing revelatory to say about golf club design. Golf ball design, on the other hand, is pretty interesting. The first golf balls from the 14th Century were made out of wood, specifically beech, by carpenters using hand tools. They weren't perfectly round and it's safe to assume that they sucked. The 17th Century saw the slight design improvement of the featherie, a leather ball stuffed with bird feathers and stitched shut. But these things took forever to make, behaved differently when vet versus dry, and were also not perfectly round.

In the mid-1800s, a guy named Robert Adams Paterson made the first molded ball. He discovered that the sap from a sapodilla tree, native to Malaysia, could be heated up, placed into a round mold and would then dry hard. Called the guttie, these were the first golf balls with mass-manufacturability, and with the added bonus that they could be reheated and re-molded if they went out-of-round.

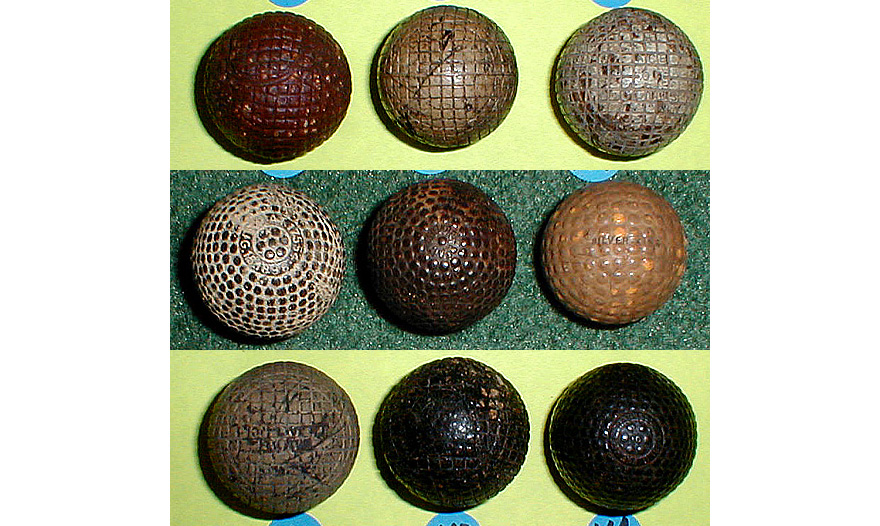

Then an interesting discovery was made. If you owned a guttie for a while, it got nicked and banged-up from regular use. People subsequently observed that when you hit a nicked-up guttie versus a brand-new one, the roughed-up balls actually had a more consistent flight path. Well before the Wright Brothers or any knowledge of aerodynamics, regular folk observed that those little nicks helped stabilize the ball in flight.

Golf ball manufacturers thus began etching, carving and chiseling different textures into guttie surfaces, trying to find the pattern most conducive to stable flight.

By the late 1890s, a new type of golf ball had been created, by accident, by a visitor to B.F. Goodrich's rubber goods manufactory. A guy named Coburn Haskell had a golf date with Bertram Work, a Goodrich superintendent, and while Haskell was waiting for his buddy in the factory, he idly wound a bunch of rubber bands into a ball shape—and by bouncing it, discovered it contained a high amount of potential energy. Work and Haskell subsequently skinned the invention with the sap from a Balata tree, and the guttie became obsolete.

Up until the early 1900s, all golf balls were patterned with raised protrusions. But then an anonymous inventor discovered that surface indentations were the way to go. Now covered in dimples, the new 20th Century golf ball could be smacked into seriously controlled flight, and pros could even put backspin on it to make it stop more quickly upon landing. (It also probably led to some theretofore unseen dramatic shanking.)

By the 1960s Balata and rubber was done away with and replaced with urethane skins and synthetic resin cores. And while that sounds boring as heck compared to some of the earlier innovations, as we shall see in the next entry, there is something surprising about the modern-day golf ball.

-

o2Favorite This

-

Q5Comment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.

Comments

no such thing as safe non safe xxx,idts

I just purchased a EC Jones cast iron golf ball press, does anyone have any info on this

I found one here recently.....one.