The Best-Looking-Ever U.S. Money was Designed in the 1890s

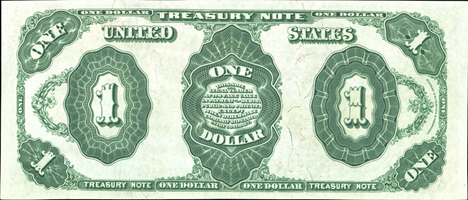

Last week, we saw the graphically chaotic mess of the U.S. Treasury's first currency designs in the 1860s. By 1890 the U.S. $1 bill was still all over the place, from a graphic design standpoint:

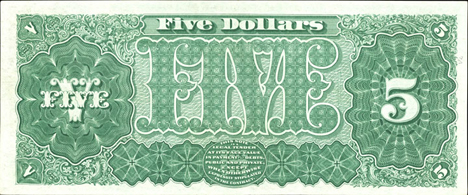

But by that same year, the $5 bill was taking on a shape remarkably similar to the one many of us grew up using. It has a centralized portrait within an oval frame and a symbol in each corner (though they're still hanging onto that Roman numeral thing).

Cool as it is, that bill remained a design anomaly and the centralized portrait would not become a standard design element for decades, though it would make an occasional appearance.

Later in the decade, however, money really started to get cool. In the late 1880s Congress had authorized the creation of special bills backed by silver, and by 1893—after a presumably exhaustive search—the Treasury's Bureau of Engraving and Printing finally settled on a small group of artists with the skillz to create these new Awesome Sauce bills. As we saw in a previous entry, carving intricate images into metal takes forever, and it wasn't unitl 1896 that their kick-ass Silver Certificate bills were ready to go. They were unlike any that had come before:

That there is the front, which is so artsy it's got a name: History Instructing Youth.

Will H. Low's design for the $1 note, entitled History Instructing Youth, shows a female History with a young student standing beside her, gesturing to an open book of history before her. An olive branch rests against the book, holding it open to show the Constitution of the United States upon the page. Both the Washington Memorial and the Capitol Dome can be seen in the background landscape. The outside border of the note shows 23 wreaths, each bearing the name of a noteworthy American - not surprisingly starting with Washington, Jefferson and Franklin, but also including such names as poet Henry Longfellow, inventor Robert Fulton, and author Nathaniel Hawthorne, among many others. The seal of the Treasury appears in the lower right.

Here's the flip side, done by different artists in the crew than Low, who probably had his hands full with the front:

The back of the 1896 $1, featuring intricate geometric lathe work and a winged, shield-bearing Liberty in each of the upper corners, carries traditionally-styled portraits of both George and Martha Washington. The portraits were engraved by Alfred Sealey and Charles Burt, respectively, and the overall design of the back was the work of Thomas F. Morris.

Take a closer look at how exquisitely intricate the carving was:

For that same year, Low had also banged out an equally artistic $2 bill design. Called Peace and War, it featured embodiments of each crossing an olive branch and a sword under a bald eagle. And check out that cannon sitting underneath War's feet.

Sadly, however, this design was rejected by Claude M. Johnson, the head of the BEP; this account claims Johnson "had strong artistic opinions" and "still wasn't satisfied with the design" despite Low integrating his requested changes.

Instead Johnson went with this alternate design, intriguingly titled Science Presenting Steam & Electricity to Commerce & Manufacture:

That year's Silver fiver was even crazier-looking, and though I cannot nail down the exact title, depicts "Electricity as a dominant force in the world."

The design of the Silver Certificates, however, did not influence the regular bills, which continued to sport chaotic and constantly shifting designs. We used red, green, blue and yellow ink alongside black; portraits got bigger and smaller and shifted sides; buffalo made an appearance; fonts with no relationship to each other whatsoever continued to crowd the bills.

There were, however, a couple of standouts. In 1907 the Treasury released this special Gold Certificate tenner, which sported a layout familiar to us today, along with unfamiliar orange ink:

There was also a $20 version:

Not to mention an even pimper version in a rather larger denomination:

That, however, was not the largest bill ever made. Here's a $10,000 bill from 1934 (the middle of the Great Depression, for chrissakes):

That same year they also created a $100,000 bill, but that was for official Federal Reserve Bank transactions only, whereas the ten-grander was actually circulated among the populace and periodically re-issued until 1946. There's reportedly over 300 of these $10,000 bills still existing, and if any of you have one, my question is: Do you like to shoot dice?

-

oFavorite This

-

QComment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.