Design Process Kills Creativity / Design Process Creates Creativity

-Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the art of Motorcycle Maintenance

I teach design process to people with very little experience in design, at a thing we call the Design Gym. The response from our attendees is always very positive. People, with this new knife of analytic thought, feel excited and energized to go and use it in their lives, to organize their thoughts and to approach their problems in a new way. When I tell other frameworks for non-designers to better understand design, the responses are sometimes controversial.

A few months back, at an Interaction Designer's meetup, I brought up what I do at the Design Gym. A new friend protested adamantly against the idea of process. He insisted that he just got in, rolled up his sleeves, and got the job done. He insisted that he followed no process at all. Plus, he derided process as rigid and no fun. And in one way, he's right: something is killed when you think about and describe what you do. He feels that a certain freedom is killed. But what is created?

One of my friends from Industrial Design school recently had me over to discuss her portfolio as she considered her options for jobs. She's been working at a design-driven consultancy for the past several years as a senior designer... and the feeling is that it's time to start getting ready for the next step. The consultancy she works at doesn't have an explicit process—companies come to them for their brand power and aesthetic. So when showing the story of a project, there are too few pieces around to speak to. There are a few sketches, then some renderings, then the object. Which is a story, after all...but it doesn't speak to the why or the how—the sort of things employers say they love to see in portfolios. I think she realized that this was a problem, which is why she had me over: to help her find and tell her story, through the lens of process.

What is created when we apply a process? When process is used consciously you have evidence of work for each part of the design process. Those groupings of work help tell the story of the project, and the decisions made at the transition points in the process.Now I think it's important at this point to acknowledge that process is, in some sense, a lie. Or at least an artificial designation. I like to illustrate this using a Norse tale I read as a boy.Loki, the trickster God, made a wager with a Dwarf while both were in heated discussion, drunk on mead. Loki was so sure of his position, that he bet his head on the wager. Loki cheated on the bet, but still lost. The Dwarf came to collect, and Loki's friends were determined that he not squelch on the wager. Loki was placed on a chopping block and the Dwarf sharpened his axe. At the last minute, Loki protested loudly. The wager was for his head, which he argued was clearly forfeit. But his neck was not delineated in the wager. If his neck was damaged at all, the Dwarf would be in violation of the terms of the bet. The disagreement was taken to Odin, king of the gods for resolution. Odin ruled in Loki's favor. He got to keep his head, tied, as it was, to his neck.

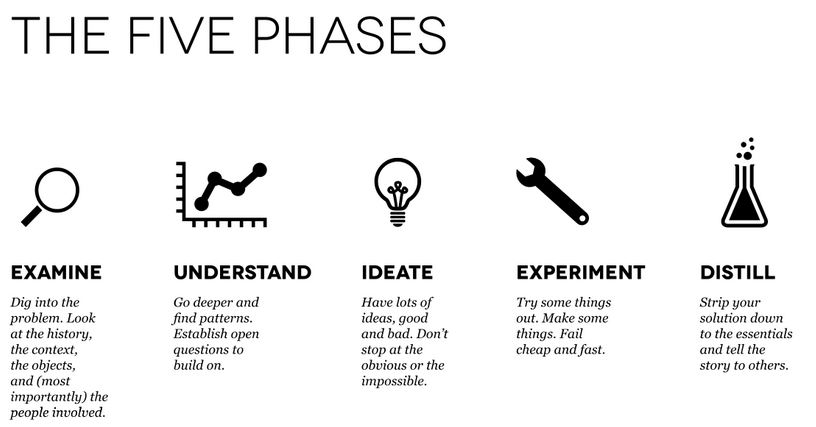

I teach a five phase design process. I advocate for a thorough research phase that we call EXAMINE as separate from an analytical or organizational phase we call UNDERSTAND. It's good to try to separate these two phases, but in real design practice, it can be hard to tell when one phase stops and the next starts.

IDEATE flows from that analytical phase, giving us solid needs and goals to work from. Having great ideas and a lot of them fuels the EXPERIMENT prototyping phase. The storytelling phase, what we call DISTILL helps make sure we stop and ensure the work we've done has memorable impact. When the time comes to talk about what you have done and what you plan to do next, you have artifacts and clear thinking from the previous four phases to draw upon in service of your story.

These five phases are a framework, and we NEED frameworks to help us process and think better. If I tell my students "have some ideas" or "solve some problems creatively" that won't work nearly as well as giving them some solid frameworks on how to ideate. I think designers need to refresh their memories on good frameworks regularly, to keep themselves sharp and to look at the work they do with new eyes. I recently had a conversation that brought this home for me.

I was having lunch with a friend of mine from design school. He's been living abroad, working for a large manufacturer of consumer electronics for almost a year. Recently, he got promoted from doing day-to-day sketching and rendering of concepts to doing more forward thinking, strategic work—design thinking, if you want to use that worn-out word.

Naturally, our talk ran into design process. I told him about the frameworks I teach to the people who come to my Design Gym classes. When I spoke about what we teach for the "Experiment" phase, I described how we teach basics of prototypes: that there are three basic types: Role, Look & Feel and Implementation and how to handle each of them. My friend stopped me and said:

Oh, right... the "what do prototypes prototype" paper [PDF]. I've read that.

I went on to describe one of the really juicy points of the paper: the difference between fidelity of a prototype and the resolution of a prototype. Fidelity is about the accuracy you believe it has to the final product. Resolution is the amount of detail you have to put into the prototype to convey purpose or believability. At this point, my friend said:

I'll have to look at that again.

I think we could all use another look at some great frameworks. My friend had a passing familiarity with this framework for prototyping. He recognized it when he saw it. But when he saw how deep it went, he knew that it could help his work. Making sure your team and your boss and your test subjects know what they are looking at, making sure you're clear on the type of feedback you're asking for and why... it's invaluable.

Those people who say they use no process, that they just get the work done... honestly, I think that can be a recipe for disaster. When we work for others or with others, we need to have a clear plan, a map for the road we're going to take together, and how we're going to get there. It's not just clients that like to know when they're going to see round two and how much it's going to cost...employees like to know, too. People who say they have no process are lying. They have, at least, a heuristic, a rule of thumb, a method, an approach.

The article on prototypes goes on to describe this space in some greater detail, clarifying that the goal of a series of prototypes is to point towards the "real thing" with greater fidelity, to begin to integrate these three distinct foci of prototyping activity. We can start at one of the poles, but as we work, we have to come towards the center. When we get to the center, to a prototype that represents what we really want to make real, we have a trail, a trail of all the prototypes we made and all the feedback we got on them. So we can be clear on why the thing is the way it is.

My friend working on her portfolio was in a particular pickle, however. After years of rockstar designer-led design, they often had just one or two simple sketches, a rendering and a finished product. They often go straight into 3D CAD design after a quick sketching sprint and design in 3D. Any changes to the model are not preserved. They get it right and make what the client wants and what the designer can deliver: great design. In my consultancy experience, we would always present mid-phase options. Three to Five directions, often defined or arranged according to some user need or design strategy.

Was this method better? To be sure, my friend has produced a hell of a lot more work than I have! But what they don't have is a story. When I tell the story of how my projects came to be, I have my process to refer back to. That's why I include storytelling as the last phase of the design framework I teach. Having a framework means you can look back on what happened in the design process and have clearer buckets for what transpired. Chunking is a great storytelling technique. Every story has a beginning, middle and an end, after all. Knowing those parts of storytelling help you tell better stories. Having a design framework doesn't just help you design better, it helps you communicate what happened better. And if someone is paying for your design work, I guarantee they will enjoy being on the inside of your process a bit more.

Is process a lie? A bit. I don't have a head and a neck, really. My fingers are not separated from my hands. But it helps to have a set of functional definitions, rules of thumb if you will, to help guide the process and to help us see better. Adding a little bit of process to your process might help you shake things up a bit.

-

oFavorite This

-

Q6Comment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.

Comments

Process: A series of actions or steps taken to achieve an end

Method: A particular procedure for accomplishing or approaching something, esp. a systematic or established one.

Method does have a "softer" feel...more open ended. But I use "process" because it implies reliable repeatability... something that business often like to feel. Note the words "achieve an end"...process is more directed. That may be a minus and a plus.

And you're very right about having clear, tangible deliverables at the end of each phase. In fact, I'd argue that this is the *purpose* of phases! Taking a pause to look back and forward and having a "real thing" to look at...even if it's a poster on the wall..is invaluable.