Book Review: The Toaster Project, by Thomas Thwaites

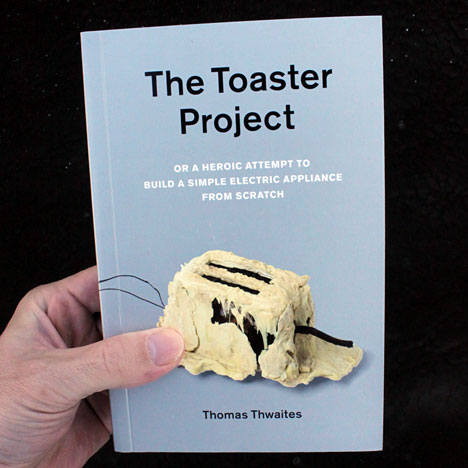

Thomas Thwaites opens his recent book with a quote from Mostly Harmless, the last book that Douglas Adams wrote in his Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy series: "Left to his own devices he couldn't build a toaster. He could just about make a sandwich and that's it." The protagonist, Arthur Dent, finds himself stranded on a planet of limited technological sophistication and after initially hoping to impress the locals with his technical knowledge, he rapidly realizes that all of his knowledge is predicated upon preexisting technology. Somewhere between a travel romp and an investigation of the modes of production in a modern capitalist society, The Toaster Project tracks his quest to build an entire appliance "from scratch." The sad little toaster he built appears on the cover and looks more like a poached egg than a modern convenience, but by the time the narrative is finished, it's pretty clear that it was a quickly-scrambled quest to get it to look like anything at all.

Henry Petroski's The Pencil is the most well-known examination of a seemingly simple technology, but Petroski catalogued the manufacturing process rather than actually mining and building a pencil. Thwaites is more ambitious, though his enthusiasm leads to compromise before nearly every insight. He begins simply enough, by reverse engineering the cheapest toaster he can find (3.94 British Pounds), only to find that it has 404 different parts. He catalogues those parts into 5 different materials (steel, mica, plastic, copper and nickel), and then sets about making a comparable appliance with a clear set of rules. The remainder of the book reads as a travelogue of the resultant exploration.

The following pages could just as easily be read as a comedic exposé, a mad quest towards a seemingly unattainable goal, or a philosophical indictment of the complexities of modern life. Thwaites's voice is most suited to the first two, and those are the pieces most likely to captivate most readers. Industrial designers may find themselves wishing for slightly more technical insight, particularly at the end, but even with those compromises towards the lay audience, for those of us who cobbled together foam models and PowerPoint slides for our thesis projects (like myself), it's pretty tough to cast the first stone at someone who actually explores what it means to make something. The most important part of any design brief is the constraints. Thwaites sets out three, which are, roughly: (1) It must be comparable to a modern commercial toaster, (2) it will be made "from scratch", and (3) it will be made on a domestic scale. After a presumably sarcastic quip (he is British, after all) that he's made a set of logically infallible rules and set them in stone, he sets about breaking every one.

The first step involves making/finding the raw materials. But what does "from scratch" mean? Thwaites quotes Carl Sagan's "apple pie recipe," which begins, "you must first invent the universe," but that's a little much for a 9-month thesis. For steel, the first raw material, Thwaits admirably begins over 9 billion years after Sagan, choosing an iron mine in Britain to mine ore in the hopes of smelting it. Of course, the hole has already been dug and he ultimately removes the ore from a display case rather than with a pickaxe, but begins to get his hands dirty right after using a sledgehammer to break the ore into pieces.

It doesn't take long before he discovers that "modern" engineering schools teach on a level far above (3) domestic scale. Engineers in 21st century schools get only slightly closer to iron smelting than Journalism students get to the CPUs that run the computers they type upon. Thwaites's has to reach all the way back to the 16th century to find a text that explains basic smelting. The resultant mishmash of modern and ancient techniques that gets him first "pig" iron and later steel involves concrete, coke (an ash/coal derivative ...though that's a different story), thermocouples, a leaf blower and in a final act of compromise, a microwave. Still, each one of the modern appliances he used as a concession were really only devices that let him complete a complex process faster.

Fortunately for him, the next material, mica, is little more than a footnote. It's a mineral, requires no smelting, and is easily chipped off of a nearby cliffside. His concessions for the next material, plastic, are a little more severe. Although he begins with the audacious goal of visiting an offshore oil rig, BP says "no." More importantly, the polymers behind plastic are far harder to make than metal. Consequently, after hand-carving a two-part mold out of wood, his attempts at making starch based plastics instead of oil plastics fail, and he ultimately turns to recycling existing plastic. It works; at least insofar as one can call the unfathomably ugly carcass of a toaster that appears on the cover a success.

From there, the next two steps are covered in far shorter chapters. He extracts copper from the tailing ponds above a copper mine using electrolysis and the chapters grow shorter as the book moves forward. The last metal, nickel, doesn't occur in Great Britain, so after an abortive discussion of Siberia, he orders copper coins from Canada and rolls those into wire out of a machine.

Based on the brevity of the final chapters, it sees that that the fourth constraint (finishing on time) trumped the first three. The last chapter, assembly, is covered brusquely, and the only obvious concession made during assembly is that he runs his toaster off of a DC battery current rather than the far more dangerous AC current in the wall. That said, the final photograph of his admittedly subpar toaster in context on the wall of a department store with a price of 1,187 pounds is punchline enough to forgive the concessions he made along the way. The Toaster Project is a bit of a [near] infinite regress. By delving deeply into every aspect of production, what appears to be an industrial design exercise ultimately ends philosophically, and can't help but leave the reader pondering "life, the universe and everything," which happens to be the title of a slightly different Douglas Adams book than the one that inspired his own "hitchhiker's guide."

-

oFavorite This

-

Q2Comment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.

Comments