Designing a Better Crime Scene Evidence Collection System

Kate Strudwick's For.Form

Exploratory designer Kate Strudwick currently works at the Google Creative Lab in London. But even when she was still a student studying Innovation Design Engineering at Imperial College and Royal College of Art, she formulated insights that would steer her towards work that combines pragmatism with exploration. Here are some examples of these insights, revealed to DropOutMag by Strudwick:

Don't design in a bubble.

"I sometimes think that some designers can focus on making work for other designers in the bubble of the design world - there is nothing wrong with this - but I try to avoid this by collaborating with non-designers on a regular basis."

Don't design alone.

"Collaboration is at the heart of my work, whether with other designers, engineers or potential users and I strongly believe good design cannot be done alone."

Don't silo problems.

"In the past, if there was an issue you would get a specialist in that area to solve that problem. However, as the problems get bigger and more far reaching there needs to be a different approach. The world doesn't need more stuff made for the sake of making it - it needs ways of thinking that can actually make a difference."

These insights, coupled with her fascination of true crime podcasts and Netflix detective series, led Strudwick in an unusual direction for her graduate thesis: She began talking to detectives for London's Metropolitan Police Service, a/k/a Scotland Yard, a/k/a "The Met."

What role could a designer possibly play in solving mysteries? Through chatting with detectives, Strudwick learned that problems often cropped up "in the initial collection and preservation of [crime scene] evidence."

We've all watched scenes on TV where a detective pulls on a glove, picks up an object, and drops it into a Ziploc or paper bag, which then gets whisked away to the forensics lab. But Strudwick learned that this basic system "has resulted in increasingly large windows of opportunity for potential contamination of evidence at crime scenes.

"Forensic techniques are progressing rapidly, utilising the latest technology, and they are becoming increasingly sensitive to contamination — both physically and from misinformation leading to misinterpretation. This means the methods of gathering and processing the evidence, carried out by the police, need to become more stringent but there is a current lack of time and money available to invest in improvements - that is why I thought it would be an interesting area to explore."

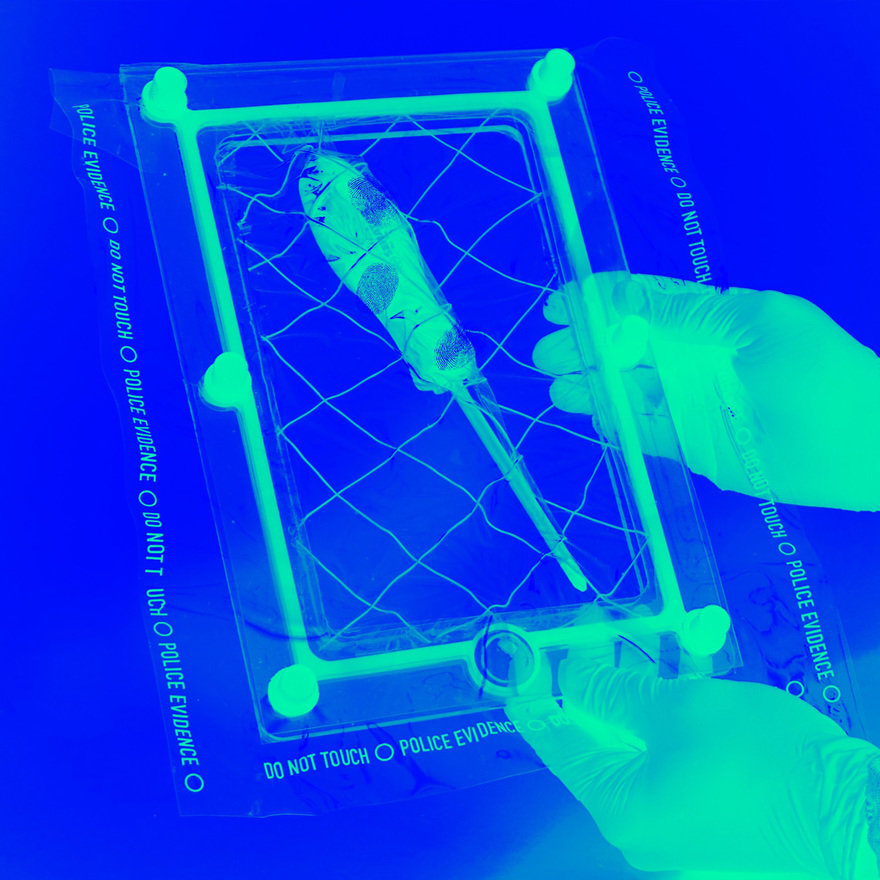

Through interviews, ride-alongs and testing, Strudwick found that the contamination of evidence was often linked to the paper or plastic bags commonly used as collection vessels. She thus designed an evidence-gathering system called For.Form, which is essentially user-friendly packaging design for detectives.

The toolkit itself consists of:

1. A novel form-able material, that can be moulded around the evidence, keeping it in place and providing a shell to which it can be returned to the exact same position after forensic examination. This material can also be formed into an initial dome-like shape to cover and protect the evidence at the crime scene.

2. A flexible weight, to weigh down the dome at the scene to create a sealed protective chamber.

3. A frame-like sealing system, to trap the material, display the evidence and create a standardised sized packaging for more efficient storage.

4. Embedded RFID chips to enable automatic tracking of evidence through the chain of custody. It can also track who has handled the evidence and when, where and how many times it has been opened and contain any important information about the case.

Here's how it works:

"It was fascinating to work with members of the police and forensic scientists," Strudwick says. "I felt like a spy being able to access parts of a world that not many people will ever get to see. They were so open and interested in the design process as, for many of them, they had not really collaborated in this way before.

"For them, looking at how evidence is packaged was a challenge that they had either thought about or investigated before, but with such busy schedules they had not had the chance to scrutinise it further.

"I think many of them began to see the potential of future collaborations with people from creative industries to bring an outside perspective on an issue that they had previously considered."

If you yourself are looking for an area to put your design skills to use, you can learn from Strudwick's example. Find things that interest you, and talk to people who work in those fields. I think you'll find a firefighter is happy to tell you about the lousy handles on a fire truck, a gardener can tell you what tasks ruin their knees, an elderly person can detail their ritual for transporting heavy groceries from supermarket shelves to their cupboards. They may or may not be Kickstarter smashes, but solving problems is what you're trained to do, and you'll find no shortage of things to tackle.

via DropOut Mag

-

o1Favorite This

-

QComment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.