Sourcing Wood for Furniture, Then & Now: The Singer Sewing Machine Company

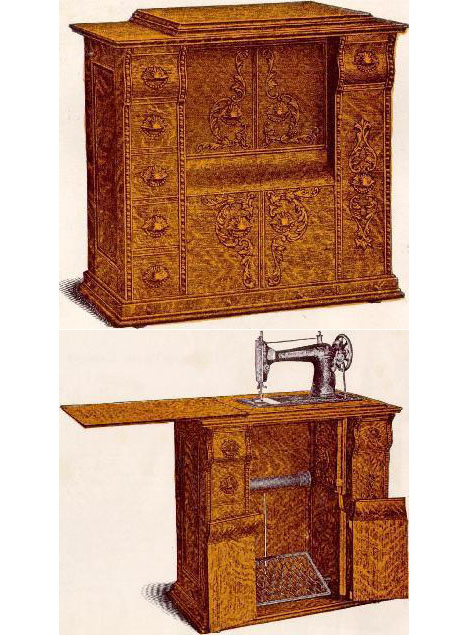

You'll probably be surprised to hear that, over a century ago, the largest furniture manufacturer in the world was...the Singer Sewing Machine Company. In the 19th and early 20th Century a sewing machine was not the small plastic thing you see today on Martha Stewart, that can be carried from room to room or tucked in a closet; it was a machine, a heavy one made of steel and cast iron, that needed to be supported in a purpose-built cabinet. And for the sake of domestic palatability, those cabinets were initially ornate Victorian pieces of furniture.

In the 1880s, America's average furniture-making company employed 11 workers each and produced some $15,000 of goods per year. In contrast, Singer employed over 1,000 in two furniture-specific factories and produced $800,000 to $1 million worth of furniture annually. Singer not only kicked off the domestic appliance category of objects with their series of machines, but completely revolutionized woodworking and mass production by turning a veritable army of talented machinists towards the science of building furniture.

By 1900, Singer had 3,000 woodworkers cranking out two million cabinets per year at just one of their two woodworking factories. Detailed accounting records for the other factory have been lost, but we can assume the output was similar. This amount of production required massive amounts of wood, far more than the cabinet-making shops of New York City and New England could provide. That was why, decades earlier, they made a decision that seems obvious to us now but was well outside-of-the-box for the 19th Century: Let's build an enormous mass-production furniture facility—hell, let's build two of them—in the middle of some big-ass hardwood forests in the Midwest. We'll save tons on sourcing.Thus, in the 1860s Singer agreed to send, on his own urging, one of their young cabinetmakers (ironically named Leighton Pine) to find suitable forests. Pine toured the midwest and selected South Bend, Indiana, as the site of Singer's superfactory-to-be. It came online in 1868.

The largely unsung Pine, armed with a brilliant imagination and the technical expertise of Singer's talented pool of production-machinery pioneers and designers, made solid contributions to the modern-day mass production of wooden furniture.

In a precursor to today's Apple-Samsung-Motorola-Google lawsuits, sewing machine companies of the 19th Century were constantly seeking ways to improve their products and production methods and routinely accused each of ripping the other off. Singer competitor Wheeler and Wilson discovered that a specially-constructed blade could be used to "shave" a thin layer of wood off of the surface of a log. This veneer could then be layered to build up a board of a desired size, cleverly multiplying the efficiency of their source forest.

Singer was keen to copy this technique, and Pine was eager to perfect it. Soon Singer had their own peeling blades, and Pine discovered you could take cheap, built-up layers of lousy pine wood and top it with a sheet of more precious walnut to cheaply make an expensive-looking cabinet.

Pine also figured out that if you crossed the layers of grain in alternate directions, it made the board stronger and eliminated the bubbling problems associated with veneers. (No one thought to call it "ply wood," but that's what it was.) And under his direction, Singer added a new element to wood production: Heat. Singer introduced steam-heated veneer-drying plates to their factories, which vastly increased the speed of the production line.

In 1880 Pine realized something else: everyone in the cabinet-making game was after walnut, pine, oak and other popular types of wood. But no one would touch nyssa, colloquially referred to as gumwood. While gumwood was fairly strong and hard, it was also elastic and had a tendency to warp badly, making it difficult to wring a finished product out of it. No one wanted it. So it was cheap.

You can probably figure out what happened next. In 1881 Singer opened their second woodworking factory in Cairo, Illinois—next to a massive stand of gumwood, which Pine had negotiated a sweet deal on. The factory's first year of production was a disaster, as gumwood lived up to its troublesome reputation. But Pine kept at it, creating new methods to master the material. (Detailed records as to his exact improvements do not exist, but we do know of this one example that Pine developed years later: He figured out, by observing a laundry-wringing machine, that you could squeeze all the moisture out of a veneer sheet by running it through two rollers. Singer engineers built the rollers and got them online, improving their production process yet again.)

By 1883 Pine had all of the problems ironed out, and that year, for the first time in Singer's woodworking history, in Cairo they had a factory whose capacty outstripped the insatiable consumer demand. Pine then used the downtime to run detailed efficiency studies of Cairo vs. South Bend and discovered that his gumwood operation at Cairo was more profitable. His dream realized, Cairo was awarded a greater share of production.

Following that, Pine tackled another new assignment. It's unclear who came up with the idea, but Pine was the one who got it to work. The discovery was made that if you steamed separate layers of this allegedly crappy gumwood, you could then press it into a shaped form and achieve extraordinary strength, rigidity and beauty. Decades before the Eameses, Singer's new, gorgeous bentwood sewing machine case covers were born and hit the mass market in 1884.

[Note: This is a highly condensed and grossly oversimplified account of Singer's contributions to woodworking and mass production in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. For anyone interested in this topic, I highly recommend reading David A. Hounsell's From the American System to Mass Production, 1800-1932; David O. Whitten & Bessie E. Whitten's The Birth of Big Business in the United States, 1860-1914: Commercial, Extractive, and Industrial Enterprise; and Ruth Brandon's Singer and the Sewing Machine: A Capitalist Romance. While you may find the books prohibitively expensive at the Amazon links above, your local library may stock them.]

-

oFavorite This

-

QComment

K

{Welcome

Create a Core77 Account

Already have an account? Sign In

By creating a Core77 account you confirm that you accept the Terms of Use

K

Reset Password

Please enter your email and we will send an email to reset your password.